Photos From The World’s Last Cave Village – Kandovan, Iran

Speaking recently to one of those authentic “I’m a tourist not a traveler” types, I was told “Nate, travel is the only thing you can spend your money on that will make you richer”. Kandovan, located in a fairly remote and dusty North-Western corner of Iran, had reminded me of this trite meme. Of course, a quality education, a carefully diversified bond portfolio, or perhaps a great work of art, are three off-the-top examples I can think of that could make you richer than travel.

And, at the end of another month in dusty Iran, being slightly travel-weary after almost one-thousand-four-hundred days of travel, I would posit that a mint condition Seinfeld box-set, a cold beer, a couple of pork-chop sandwiches and big-screen TV would all make my life much richer.

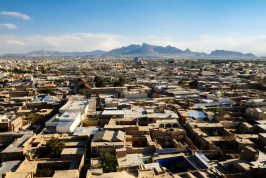

In any case, Kandovan is yet another Iranian village that appears more movie set than real-life. Visually unparalleled, culturally unique, around one-hundred and seventy troglodyte families reside inside insect-like cave homes – their multi-level abodes carved directly into a deep volcanic rock. The source of the ancient lava is nearby Mount Sahand, a towering volcano stretching almost four-thousand meters into the sky. Formerly erupting on-and-off for around twelve million years, fortunately, Mount Sahand is now dormant – but the lava digging continues on.

From around seven centuries ago, the families still living in Kandovan can trace their roots back to the days of Genghis Khan and the invading Mongolian empire. It’s a genuinely spectacular spot, with snow-capped mountains surrounding the village, and over seventeen summits in the nearby Sahand range taller than three kilometers. On the green slopes directly opposite, painterly terraced farms add colour to the earthy tones, smoke rises gently from BBQ restaurants and wood-fired kettles below, a clear river runs on by, the air is crisp, and everything seems slightly surreal and, well, Flint-stoney.

Certainly, Kandovan is already a tourist attraction. On the day I visited, a local pointed at the labyrinth of caves and excitedly told me “there’s some Americans here! You should talk to them!”. Alas, although I heard a few distant calls of “does anyone have the Wi-Fi password?”, I didn’t get to meet them. The only tourists I saw were hundreds of Iranian school kids, reminding me of my youth back in Australia, where we have a distinct lack of centuries-old-lava-carved-cave-villages, so each year our school excursion was a visit to a working animal slaughter-house. In any case, there were a small handful of Tabrizi tourists – mostly women shopping for hand-made carpets, honey, and camel-hair socks. This being Iran, that meant an inexplicable number of selfie invites.

Maybe I got lucky, as I’ve read that Kandovan really is a popular tourist attraction. However, during the several hours spent walking the quieter upper-levels and slippery sheep-trails high above the settlement, I didn’t see another soul – other than the occasional cave-dwelling local.

Being somewhat similar to well-known Cappadocia in Turkey, comparisons between the two cave settlements are inevitable. The key difference is that Cappadocia has gone full-tourist, with regular cave-life being completely abandoned long ago, traded for a fist-full of tourist dollars and a nice McMansion in the neighbouring village. I’m not disparaging Cappadocia – I visited not so long ago and it remains one of the most striking places I have ever seen.

Kandovan in Iran is different – it’s real, and alive. And despite Kandovan being well visited by Iranian day-trippers, this genuinely remains a working village – filled with cave-people just hanging out watching TV in cave houses, and occasionally knocking on the front door of the neighbours cave to borrow a cup of sugar because the local cave convenience store shuts at five.

With such genuine historical continuity, you would assume a UNESCO World Heritage listing is in place. However, UNESCO has some “issues” with Kandovan. There’s some angst about the contemporary stone and brick additions to Kandovan, as they’re not part of the “original” fabric of the cave village. UNESCO sees these structures as a problem that needs resolving, prior to Kandovan being admitted onto the World Heritage register. On the other side of this UNESCO story, are the people of Kandovan. They’ve carved-out not only their own domiciles, but also make a seemingly viable living from the tourists that do make it here, with locals earning a Rial or two via restaurants and locally hand-made tchotchkes.

Indeed it could be debated, the addition of these stone and brick structures and the several tourist-targeted galleries have actually enhanced the authenticity and experience of Kandovan, giving the whole place a naturalness and normalcy, in totally surreal surroundings. Ram-shackled, and somewhat raw, the organic evolution of Kandovan is now somewhat ironically contemporary. The layering of old and new is effortlessly pure. A sanitised, by-the-book, UNESCO-friendly version of Kandovan would certainly not have the same feeling, or appearance.

The question then becomes – do the traditional owners of this cave village have rights? Is the subjective “authenticity” of Kandovan of relevance and concern to anybody other than the people who live inside the caves of Kandovan? Or, is this settlement simply too valuable on a world-scale, and therefore must be protected and preserved at any cost? Whether or not to put the perceived needs of international visitors ahead of those families that have lived inside for generations, is a complex question.

The concept of authenticity with regards to tourism is fraught with questions of endless controversy, and the only answers ultimately rest on personal opinion. The representatives and residents of Kandovan could look around the world for a glimpse into their future, as many hugely popular tourist attractions already face these issues on a daily basis.

My personal whipping-boy, Dubrovnik, is a prime example – the historical Croatian city now has almost zero local families living within its old walls, the town is strictly maintained for tourism, and rented out to film and television studios. Inside the historical arched malls of Istanbul’s famous Grand Bazaar, the architecture remains as it always was, but these days most shops exist explicitly to capture the tourist dollar.

Once war-ravaged cities across Europe have been rebuilt, recreated and re-manufactured. Whether this is good or bad, is of personal opinion. But, all of these destinations remain hugely popular with tourists, and they’re impressive for sure. Notably, they’re also examples of the tourist-pandering end-game, the ultimate price being whatever existed before, has been changed forever.

The thing is, there is perhaps no tourism venture more authentic than the millennia-old racket of locals making a sly buck from gawking out-of-towners. Crass, but true. Even in a low-tourist area like North-west Iran, the tradition of profiting from visitors dates back to times older than Kandovan itself. Tourism and unfettered capitalism, go hand-in-hand.

With the remote corners of the world being more accessible than ever before, as tourists continue to roll in, Kandovanians are going to make money – that much is certain. However, only those locals with foresight will be aware of the true price that will eventually be paid. Whether that price is worth it, or not, is another question.

As it stands right now, Kandovan is incredible. The recent structural additions and the ventures of locals servicing tourists, in my opinion, give the village a touch of ordinariness – a nice contrast and addition to surroundings that are anything but ordinary. Only the most jaded world “travellers” could be concerned about the less “authentic” capitalistic and contemporary elements on the rocky streets of downtown Kandovan.

For us mere tourists, Kandovan is a day-tripping dream.

Nate

PS, the FINAL Yomadic Iran Untour for 2016 is now 50% sold out. All the details are right here.

Is this somewhere that the Untours will be going?

Not this year, Caroline. Perhaps in 2017 – we’re trying to figure out a route, but nothing concrete at this stage. But, we have plenty of cool villages to explore in 2016, you will be amazed at just how much there is to see in Iran.

Wow, this is fascinating. Thank you for sharing.

You’re welcome, Jennifer.

Great story & commentary, Nate, and terrific photos! My fav: “truly free-range chickens”. We’re ready to see this place.

Cheers John!

“Does anyone have the wi-fi password?” hahahahahahaha……….#f***youken

Ha! I swear I wasn’t thinking of Ken when I wrote that.. ;)

Haha, yes, Wi-Fi is essential nowadays Lols.

Anyway, nice post, I’ve never known about this if you didn’t write it. Did u enter one of the house?

Indeed, Timo! I had a quick look inside a couple of structures that were being used as shops – but spent most of the day just roaming around.

Stunning photo! It is nice to know what is the typical day looks like for Iranian locals.

What cool photos! Really interesting article about what it is like to live like the locals.

Thanks Megan.

Real diferente way of living. Nice pictures

This is a great place to visit. Clean air , no pollution and beautiful nature. If you travel to iran you have visit there

Armin from iran

Very Unique place with beautiful people.The Pictures are stunning.Thanks for this post.

AWESOME! thanks for sharing…

It looks like Kandovan has become way busier than your last visit. I was just there a week ago and there are a TON of people. Iranians obviously, but damn it was busy. I often had to wait in line to take a photo of something…

Kandovan Update: 28th September 2017, I’m here again (staying overnight this time), there are very few tourists. Not many Iranian tourists, not many foreign tourists. Seems like it might be luck of the draw…

Wow! A very stunning article. From now on I was like I want to be in this place. very well done you made your readers interested and your photography is very good !